Nautical Tourism in the Lastovo Islands Nature Park, Croatia

Association for Nature, Environment and Sustainable Development (SUNCE), Croatia

Authors: Z. Jakl, I. Bitunjac, G. Medunic-Orlic

Download case study as pdf-file.

.

2.1. Geographic and Biophysical Setting of the Lastovo Islands Nature Park

2.2. Administration and Demography

3.1. Livelihoods and Migration

4.1. Agriculture and livestock

4.4. Tourism and Nautical Tourism

5. Tourism and Lastovo Nature Park

5.1. The local tourism framework

6. The Protected Area (PA) Management System

6.1. Management of the Lastovo Islands NP and the role of stakeholders

6.1.2. Stakeholder Participation

7. The Future of Nautical tourism development

8. Conclusions: The CSO vision

.

The Lastovo Islands (Source: Igor Karasi)

.

The Lastovo Islands Nature Park (Lastovo Islands NP) was one of the first protected areas to be designated in Croatia, established in 2006. The area has been able to preserve its natural and cultural heritage due to the fact that it is an isolated and distant archipelago that was a closed military zone until the 1990s. In the last two decades the Lastovo Islands have begun to develop their economy, which is primarily based on tourism, followed by fisheries and small-scale agriculture. The number of tourists visiting the archipelago is increasing each year, especially the number of nautical tourists, who are attracted by the well-preserved nature, numerous coves and bays and good fish restaurants. Infrastructure and tourist facilities are not well developed and more construction is expected in the future, bringing with it increased pressure on the environment in coves and bays where the installation of new mooring facilities is planned. The Nature Park is currently in the process of developing physical and park management plans to establish the basis of future tourism development and management. Here we explore how ecological economics could be used to support decision-making for the sustainable development of the Lastovo Islands.

Keywords: Sustainable tourism, nautical tourism, marine biodiversity, fisheries management, depopulation, landscape value, physical planning, property rights, protected area management, carrying capacity, resilience, local communities, public participation, entrance fees, willingness to pay, economic instruments for tourism management.

.

2.1. Geographic and Biophysical Setting of the Lastovo Islands Nature Park

In Croatia, the Lastovo Islands NP is situated in the southern part of the Adriatic Sea (Figure 1). The archipelago consists of the main island Lastovo (40 km2) and more than 40 small surrounding islands, islets, rocks and reefs. Lastovo Island, with its surrounding waters and islands, was officially declared a Protected Area (PA) and named the Lastovo Archipelago Nature Park on 29th September 2006 under category V of the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). The surface of the whole PA measures 195.83 km2, out of which 52.71 km2 is on land and the remainder at sea (143.12 km2). It is the second biggest marine PA in Croatia and its borders extend to a minimum of 500 m from the Islands’ shorelines. Lastovo Islands NP is also part of the Ecological Network and very likely to become part of the Natura 2000 Network.

Figure 1: Lastovo Islands NP (Source: Z.Jakl)

The climate of the Lastovo Islands is typical of the Mediterranean, with predominantly mild moist winters and warm, long and dry summers (Table 1). They receive around 2700 hours of sunshine per year, ranking them one of the sunniest places in the Adriatic Sea. Annual rainfall is approximately 650 mm.

Table 1. Lastovo Islands NP climate (Source: www.croatia-travel-guide.com)

|

|

Jan |

Feb |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Dec |

| Maximum temperature |

11 |

12 |

14 |

17 |

22 |

25 |

28 |

28 |

26 |

21 |

17 |

13 |

| Minimum temperature |

5 |

6 |

8 |

11 |

15 |

18 |

21 |

21 |

18 |

14 |

10 |

7 |

| Number of sunny hours per day |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

10 |

9 |

7 |

4 |

3 |

| Number of rainy days |

11 |

10 |

9 |

8 |

7 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

6 |

9 |

11 |

13 |

| Sea temperature |

13 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

17 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

22 |

21 |

18 |

15 |

.

The landscape is formed of small forested hills and small valleys with high-quality soil which is used for small-scale agriculture (mainly grapes and olives). It is one of the most forested islands in the Adriatic, with roughly 60% of its surface covered by forest (Figure 2). A considerable part of the forest is old-growth Aleppo pine (411.83 ha) but there are also rare Holm oak forests (234.48 ha). More than half of the forest surface is local community property while the other half is State owned and managed by the Croatian Forest Authority.

Figure 2: NP Lastovo Islands (Source: I. Carev)

Figure 3: Red coral (Corallium rubrum) (Source: H. Čižmek)

.

The Lastovo Islands NP is important for marine and predatory birds, and is situated on an important migratory route to Africa. The Island has rich and unique flora and cave fauna, and the shallow waters of the coast and around the small islands are rich in marine life (Figure 3). Although they have experienced a decline in fish stocks, the waters are still one of the richest fishing grounds in the Adriatic Sea. There are no surface waters, but there are several freshwater ponds and seasonal submarine freshwater springs (“vrulje”) as the Island is part of a complex karst system of underground waters.

|

Rich Heritage of the area Ecological

Cultural

|

.

Besides its natural heritage, the Lastovo Islands also have a rich cultural heritage. The first human presence dates back to over 8000 years BC. The main island called Lastovo is 80 km away from the Croatian town of Split and 95 km from the Italian coast. This central southern position in the Adriatic Sea has given it special status since at least Roman times. Its strategic importance attracted a variety of foreign rulers (Greece, Roman Empire, Venice, Italy, France, England, Austro-Hungarian Empire,Yugoslavia). Between the two World Wars the area belonged to Italy. Holding a strong sense of individual identity and a need for independence, the archipelago holds many traditions that testify to the rich history of this area. The historic settlements of Lastovo and Lučica are considered monuments with a large number of churches, buildings and archaeological findings protected as cultural goods (under the Act of protection and conservation of cultural goods O.G. NN 69/99, 151/03, 157/03).

Figure 4: Old church (Source: B. Berković)

Figure 5: Amphora (Source: Z. Jakl)

Around the Island there are also 18 underwater archaeological sites. Due to its unique and rich natural and cultural heritage (Figures 4 and 5) the WWF nominated the Island as a priority conservation area of the Mediterranean in 2002.

.

2.2. Administration and Demography

The Lastovo Islands NP falls under the administration of the Municipality of Lastovo, located on the main island of Lastovo, within Dubrovnik-Neretva County. On September 29th, 2006 the Croatian Parliament declared Lastovo and its surrounding islands a protected area, naming it the Lastovo Islands NP.

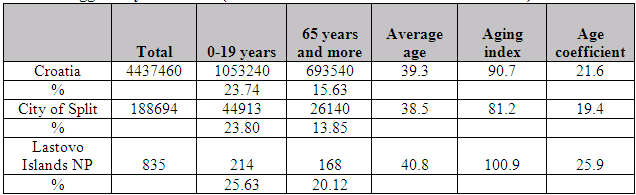

There are 835 inhabitants registered on the Island according to the 2001 population census, although in winter the population falls to less than 500. Many inhabitants, although registered there, spend winters in the cities of Split, Zagreb or Dubrovnik. The inhabitants occupy several small villages on the Island: Ubli (also a ferry port); Pasadur; Zaklopatica; Skrivena luka; Lučica; and Lastovo, the biggest settlement with 200 inhabitants (Figure 6). The number of inhabitants is decreasing however, especially the younger working population. The ratio of active (employed) to supported (unemployed) people is 19:10 which means that 65.52% of the population works (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2. Population of the Lastovo Islands NP in 1971-2001 (Source: State Administration Office in Dubrovnik-Neretva County)

Note: Pasadur and Zaklopatica were registered as separate villages only in 1991.

Note: Pasadur and Zaklopatica were registered as separate villages only in 1991.

.

Figure 6: Lastovo village (Source: I. Carev)

Figure 6: Lastovo village (Source: I. Carev)

.

Table 3. Lastovo Islands population structure compared to the national average and the second biggest city in Croatia (Source: Croatia Central Bureau of Statistics)

On Lastovo Island there is one primary school with around 80 pupils and a kindergarten. After finishing primary school pupils must move to the town of Split or the island of Korčula to continue to higher education. Due to the lack of employment possibilities many remain on the mainland after finishing their education.

In 1945 the Island was declared a military base of Yugoslavia and the arrival of foreign citizens forbidden until 1988. Due to the military atmosphere Yugoslavian citizens also avoided Lastovo. After the 1988 political changes in Yugoslavia started. In 1991 Croatia declared independence, war with Serbia began, and in 1992 the Yugoslav army left Lastovo Island. Normal life was established only after the end of war in 1995.

These facts, together with national policies that neglected the Islands, resulted in a long-lasting process of depopulation. Depopulation implies potential loss of human and social capital, but also potential biodiversity loss, as depopulated areas are more likely to be intruded upon by investors, tourists, or seasonal inhabitants who hold different values and knowledge. They are usually not concerned with sustainability of the local environment, since they do not depend on the environment as permanent inhabitants do. Without a young working population it is therefore very hard to bring new ideas and implement conservation measures. In this context, well-managed tourism has been perceived by locals and the government as the best prospect for economic development that could reverse the depopulation trend.

.

3.1. Livelihoods and Migration

As the limited natural resources of the Islands and their remote location have only offered a marginal existence, many residents migrated not only to the mainland, but even further to Australia and the Americas. The largest migration took place after the Second World War, but this trend is still very much alive. Those who have remained on Lastovo Island are engaged mainly in agriculture, cattle breeding and fishing. Currently, the main economic activities are agriculture, fishing and tourism-related services. Traditional small-scale fishing, wine-making and olive oil production form the basis of the local economy, based on a centuries-old way of life. Olive oil and wine are produced by individual households and in socialist times a cooperative was set up for the production of wine. Households still deliver their excess grapes to the cooperative that produces bulk wine. Apart from few small shops, cafés, restaurants, contractors, workshops and service providers, there are no enterprises or industries. Local government, with around 20 employees, is the biggest single employer.

.

One of the limits to further development of Lastovo is the Island’s infrastructure. The public transportation system and ferry connection to the mainland are insufficient, as are the water supply system, wastewater treatment and waste management systems. The public utility company “Komunalac”, based in Lastovo, is in charge of the water supply and waste management. However, problems with water supply are frequent in summer. In the near future, there are plans for supplying water to the Island by a regional water supply system, connected by underwater pipes to the Neretva River (water source). There is a desalinization facility on Lastovo Island (in Prgovo) but it is often not functioning.

Figure 7: Pasadur (Source: Petronije Tasić)

Figure 7: Pasadur (Source: Petronije Tasić)

Waste and wastewater flows are significant problems in isolated areas of Croatia such as the Lastovo Islands. On the main island, solid waste is collected three times a week and transported to the roadside Sozanj dump, located between Lastovo and Ubli. The municipal authorities selected this location in 1997. Situated near the coast above one of the richest underwater locations on Lastovo, the dump is in the process of closure under a national plan to transport waste to the county waste management centres on the mainland. However, this system is not functioning yet and waste is still illegally dumped on numerous sites.

Litter from yachts and wastewater discharge from yachts and coastal settlements into enclosed bays pose serious threats. A small proportion of wastewater from the village of Lastovo is channelled to a communal septic pit which then discharges it directly into the sea near Lučica port. The majority is collected by private septic tanks (“black pits”) many of which are porous and discharge either into the ground or into the sea. Hotel Solitude and part of the village of Pasadur (Figure 7) discharge their wastewaters via an undersea pipe that releases its waste just off the coast into the nearby bay.

In addition to the above-mentioned problems, forest maintenance and forest fire-fighting is poorly organised and implemented. Major forest fires in 1971 (1600 ha), 1998 (221 ha) and 2003 (494 ha), destroyed a significant proportion of forest, leaving the southern part of the

Island seriously damaged (Figure 8). At the same time that fires in Lastovo Islands NP were burning, fires also broke out on other Croatian islands. This area was not considered a priority and therefore did not receive the necessary help from the mainland.

Figure 8: Southern side of Lastovo Island burned by forest fires (Source: I. Karasi)

Figure 8: Southern side of Lastovo Island burned by forest fires (Source: I. Karasi)

The environment of the Lastovo Islands has so far managed to sustain itself in spite of these pressures, but with expected construction and tourism activities growth, infrastructure and nature conservation investments will be necessary to preserve the quality of the environment.

.

The local culture tends to be conservative and individualistic. Community-based initiatives are rare. However, in times of imminent threats the islanders are able to organize themselves. Earlier national strategies proposed PA designation, but due to the local community objections and a lack of national funds, these proposals failed to materialise. The reasons for the local community’s resistance to PA designation were fears that the Islands would again become an economically closed zone and overall distrust towards local and national government. In 2001 a local businessman planned to construct a stone quarry on Lastovo Island that would yield much profit, but with a great deal of destruction to the coastal zone. After intensive communication, lobbying activities and a “battle” with interest groups, the local NGO Spasimo Lastovo (Save Lastovo) and the Association Sunce managed to change the attitude of the community and the government, initiating the process of declaring the Islands a Protected Area and stopping the development of the stone quarry.

This event, in which local people united in opposition to the destruction of the environment is a clear illustration that islanders attribute high value to the local landscape. Yet it also shows how vulnerable the Islands are to initiatives that promise new investment at great environmental expense. PA status was declared largely in order to stop the stone quarry project, proving that residents of the Islands were in favour of conservation and wanted to develop its economy in a way that would allow a more equitable distribution of gains across the population. As national and local tourism had come to be perceived as the best opportunity for economic development, the majority of locals were in favour of the PA declaration at the public hearing in December 2004. However there is much doubt over the competence of the Lastovo Islands Nature Park Public Institution, the state institution responsible for the management of the area, which is very young (established in 2007) and still lacks the capacities (in terms of human capital, funds, and political support) to carry out its work properly.

.

As mentioned before, the local economy is based on agriculture, fisheries and tourism, with tourism taking the leading role. Pressures from tourism-related construction are mounting. Furthermore, there are many unresolved land ownership disputes so that assertions about the land categories and property rights must be dealt with carefully (Table 4).

Table 4. Lastovo Islands NP land type and ownership (Source: Nature Park Lastovo Islands, baseline study for the declaration of protected area, State Institute for Nature Protection, 2005)

| LAND CATEGORY | PRIVATE PROPERTY (ha) | STATE PROPERTY (ha) | TOTAL (ha) | % |

| Plough land and gardens | 210 | 7 | 217 | 4.09 |

| Orchard | 110 | 7 | 117 | 2.21 |

| Vineyard | 65 | 4 | 69 | 1.30 |

| Pastures | 304 | 1070 | 1374 | 25.91 |

| Agricultural land (total) | 689 | 1088 | 1777 | 33.51 |

| Forest land | 1792 | 1349 | 3141 | 59.24 |

| House gardens | 3 | 1 | 4 | 0.08 |

| Roads and paths | 23 | 2 | 25 | 0.47 |

| Constructed land | 8 | 6 | 14 | 0.26 |

| Other | 26 | 314 | 341 | 6.43 |

| Built up area (total) | 60 | 323 | 384 | 7.24 |

| TOTAL | 2541 | 2761 | 5302 | 100 |

.

4.1. Agriculture and livestock

Agricultural land on Lastovo Island is divided into small plots, precluding modernised and larger-scale agriculture. Furthermore, a shift from the state-controlled to the open-market economy, unresolved property rights and a lack of young working population today mean that only a small proportion of arable land is under cultivation (Figure 9). On the Island there are only 29 people directly employed in agriculture. However, local families usually grow crops on small plots, either for their own consumption or for restaurants catering tourists. According to the available data, there are around 14 000 olive trees on Lastovo. The second most important crop is grapes, used for wine production. Almonds, figs and vegetables (potato, onion, garlic, tomato) are also grown. Agriculture has little negative impact on the environment.

Figure 9: Lastovo Island land use overview (Source: Z.Jakl)

People from the Lastovo Islands have not been very much involved in stockbreeding in the past and this activity is today even less relevant. In total there are about 400 sheep and goats on the Island, most of which are unfenced and unsupervised. As a result, the animals’ presence is sometimes unappreciated due to their tendency to graze on native vegetation, and roam into the path of cyclists and hikers. Local breeders similarly do not like to have tourists walking in areas where livestock is feeding.

.

Fishing has always been an important source of income as the waters surrounding the Lastovo Islands are rich in marine life. A fish processing factory existed in the period 1933-1969, but was closed down when production became unfeasible after subsidies from the central government ceased, along with most of the fish processing factories in the Croatian part of the Adriatic Sea. Today most fishing is at the service of tourism. Residents are engaged in small-scale fishing, while recreational fishing is practiced mainly by visitors. In 2004, 484 licences for sport recreational fishing, 101 licences for small fisheries and 40 economic fishery licenses were purchased.

Figure 10: Spiny lobster (Palinurus elephas) (Source: Z. Jakl)

Figure 11: Zaklopatica bay (Source: P.Tasić)

Lastovo Islands NP waters are important fishing grounds for the spiny lobster (Palinurus elephas) (Figure 10) but also for other species of fish and crabs. There is one purchasing station for fish in Zaklopatica (Figure 11) that deals mainly with local fishing vessels. Fish is then sold to restaurants visited mainly by tourists from yachts during the high season. In other periods it is sold to the cities on the mainland.

In the Lastovo Islands, as in the whole of Croatia, fishery statistics are poorly collected so it is difficult to develop a well-informed report on the state of fish stocks. But the opinion of those engaged in fishing is that fish stocks are declining. This is attributed to the poor control of illegal fishing by locals and people from other islands. There are increasing numbers of Italian fishing vessels buying fish directly from Croatian fishermen and illegally fishing in the Croatian maritime zone. One objective of the establishment of the PA is to improve fisheries management. Fishing in PAs is subject to regulations that delimit the fishing area, control the use of fishing gear and the amount of fish caught. However, a very small percentage of PAs include no-take areas. Over-fishing and illegal fishing, including that of red coral, still pose a high level of threat to marine resources, both in PAs and non-PAs.

.

Hunting is practiced in the forests and pastures of Lastovo Island but on a small scale. The main hunting targets are the brown hare (Lepus europaeus), rock partridge (Alectoris graeca), common pheasant (Phasianus colchicus) and other birds.

.

4.4. Tourism and Nautical Tourism

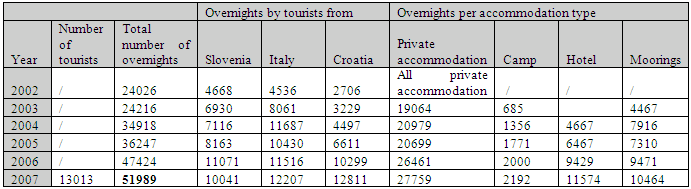

Tourism is one of the main drivers of the Croatian economy and it is likely to remain so in the future (Table 5). Nautical tourism (tourism that involves travel by sailing or boating and related activities such as fishing or diving) is the most important sector of tourism in the Lastovo Islands.

Table 5. Tourism statistics in Croatia in the period 1980-2008 (Source: Ministry of Tourism www.mint.hr)

| 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | |

| Number of tourists (in 000) | 7.929 | 10.125 | 8.498 | 2.438 | 7.136 | 9.995 | 10.384 | 11.162 | 11.260 |

| Number of overnights (in 000) | 53.600 | 67.665 | 52.523 | 12.885 | 39.183 | 51.421 | 53.006 | 56.005 | 57.103 |

| Income in billion Euro | 6 | 6 | 6.7 | 7.4 | |||||

| Income in billion USD | 1.3 | 2.7 | |||||||

| Percentage of national GDP | 7.2% | 15% | 19.4% | 19.4% | 18% | 15.7% |

.

In 2007 in Croatia there were 811 000 registered nautical tourist arrivals (7.26% of the total number of tourist arrivals) out of which 91.9% were foreign tourists (Germans 25.3%, Italians 22.5%, Slovenians 15.6% and Austrians 14.6%). In total they realized 1 378 000 overnight stays, 98% of them in the period from April through September (Central Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Croatia, 2008). The total number of licenses issued to foreign vessels for sailing in Croatian coastal waters in 2007 (excluding vessels hired in Croatia) was 54 864, and the average length of time spent in Croatia was 16 days. It has been estimated that nautical tourists spend 48% more on average per day than other types of tourists (tourist on rented boats spend 139 euro/day, on private boats 55 euro/day, other tourists 49 euro/day).

There are issues with statistical data collection, however. Every tourist arriving to a nautical tourism harbour is registered as one new tourist arrival to Croatia, but since nautical tourists usually visit more than one harbour, the official number of such tourists is likely to be higher than their real number. On the other hand, anchoring in Croatia is allowed in almost every bay and cove without any monitoring, so tourist overnight stays that take place outside of nautical tourism harbours are not registered. In this light, the real number of overnights is likely to be higher than the official one. In any case, the trend is clear. Nautical tourist arrivals and overnight stays have increased. The annual growth rate for the period 1996 – 2004 was around 15%, which was 4.1% more than for other types of tourism. Nautical tourism is expected to continue growing in the future. The Croatian Nautical Tourism Development Strategy projects that in 2018 Croatia will generate 2 billion € from nautical tourism.

Croatian nautical tourism is recognised as possessing many assets: a clean sea, a beautiful landscape rich in biodiversity, the geographical position, traditions and the perception of safety in the country. But serious shortcomings lie in the low number of moorings, lack of moorings for bigger yachts, quality of services for tourists, “value for money”, poor waste and waste-water management, and a poorly defined legal framework. Croatia has 12.2% of the Mediterranean coastline and 33% of the coastal length of all Mediterranean islands, and therefore much potential for nautical tourism development. In 2007 Croatia had 70 nautical tourism harbours and 15 areas with anchoring and buoys distributed across only two counties (Primorsko-Goranska and Zadarska County). In total there were around 21 020 moorings in Croatia (15 834 at sea and 5 186 on land). Based on the current county physical plans the number of new moorings planned by 2015 is 33 655 (25 755 at sea, 7 900 on land), which means an increase of 160%. So, in 2015 Croatia could have 54 675 moorings in total (41 589 in sea, 13 086 on land). This will require much heavy building, especially in Istria County and in Dubrovnik-Neretva County, where 43% and 22% of new moorings are planned, respectively.

Since the greatest attraction for nautical tourists is the well preserved natural environment, it is to be expected that conflicts might arise as capacity expands. County physical plans anticipate the construction of new ports and moorings in PAs, including the Ecological Network and future Natura 2000 Network areas. As projects get underway and investors begin work to define the total number of moorings and their distribution per location, they will have to develop strategic environmental impact assessments that include feasibility assessments of physical plan derogations, impacts on the natural and historical heritage, and hopefully, the input of local communities.

Croatia has several new laws and regulations defining procedures for strategic environmental and nature impact assessments (Regulation on Strategic Assessment of the Impact of Plans and Programmes on the Environment O.G. 64/2008, Regulation on Informing Public and Interested Public in the Environmental Protection Issues O.G./2008, Regulation on the Environmental Impact Assessment O.G. 64/2008, Rulebook on the Nature Impact Assessment O.G. 89/07, Environmental Protection Act O.G. 110/07, Nature Protection Act O.G. 139/08). However, these regulatory tools have unclear and overlapping competences and are still not properly functioning in practice. In addition, they are often modified by the Croatian Government. For example, the Regulation on the Environmental Impact Assessment entered into force in June 2008, but by April 2009 its strength in terms of environmental protection and public participation had been diminished, allowing investors to be less concerned with the environment.

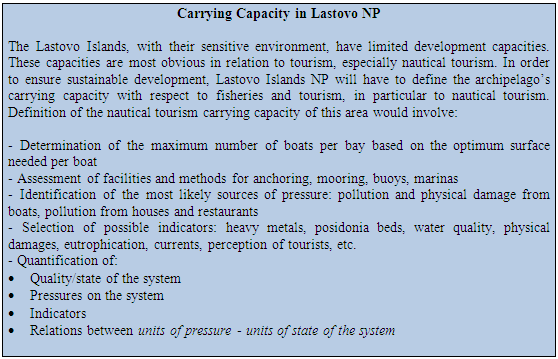

The greatest threat for the long-term nautical tourism development is the potential for uncontrolled usage of natural landscapes and resources. Tourism, including the nautical tourism sector, generates direct economic benefits and contributes significantly to the country’s foreign exchange earnings. Nautical tourists visit Croatia because of its attractive coast, the large number of islands as well as preserved coves and bays free of urbanization. More than 90% of the current nautical tourists in Croatia have already visited Croatia at least once before. The Islands currently have approximately 2.6 moorings per coastal kilometre. If sustainable nautical tourism development is to be adopted, any construction of new mooring facilities has to respect carrying capacities (the amount of use an area can sustain while maintaining its productivity, adaptability, and capability for renewal) of coves, bays and ecosystems in general in order to avoid destroying the main assets that are attracting tourists.

.

5. Tourism and Lastovo Nature Park

5.1. The local tourism framework

Almost all economic sectors (e.g. agriculture, fishing) on the archipelago are related to tourism, reflecting national level designs for its economic development. This affects social life since the Islands are almost deserted during the year and only come to life in the summer period. Tourism has actually only been developing in the last 15 years, since the war, and the Lastovo Islands are mostly visited by families in search of quietness and unspoiled nature. The number of tourists has increased significantly, although still not as rapidly as in other coastal parts of Croatia.

This is due to several reasons: the distance of the islands from the mainland and poor ferry connections, with the only regular access from Split by ferry (5 hours) or by catamaran (3 hours); limited marketing of the island, a lack of sporting and cultural events; the existence of only a few sand and pebble beaches; and poor infrastructure.

In 2005 there were more than 70 registered owners renting apartments to tourists. Currently on the island there are 511 registered beds in private accommodation, 30 registered (legal) moorings, 30 camp units (for up to 100 people) and 72 hotel rooms (hotel “Solitudo”, “A” category, 150 beds). Two lighthouses, one on Lastovo and one on Sušac, are also being rented.

The “sun and beach” tourist season is limited to July and August, while nautical tourist season usually runs from June to early October. In 2007 the total number of overnight stays was around 50 000 (Table 6), out of which most were Croatian, Italian and Slovenian tourists. Fewer than 30 000 overnight stays were in private accommodation, while the rest were in campsites and hotels, with an additional 10 000 or so mooring fee payments (fees are paid by boat per night, but the price also depends on the boat length). However, many tourists are not registered at the Tourist Board by their hosts who wish to avoid paying sojourn and income taxes. Likewise, many nautical tourists who anchor do not pay mooring fees and are therefore not registered, although in recent years statistical coverage has improved.

Table 6. Number of overnights in Lastovo Islands NP in 2002-2007 (Source: Lastovo Tourist Board office statistics)

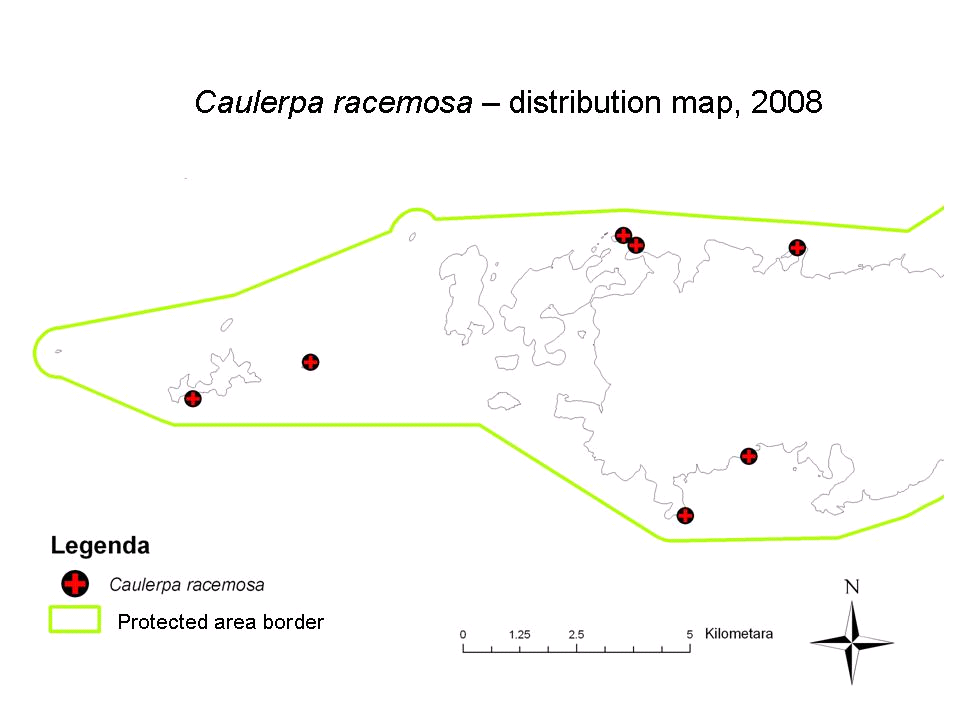

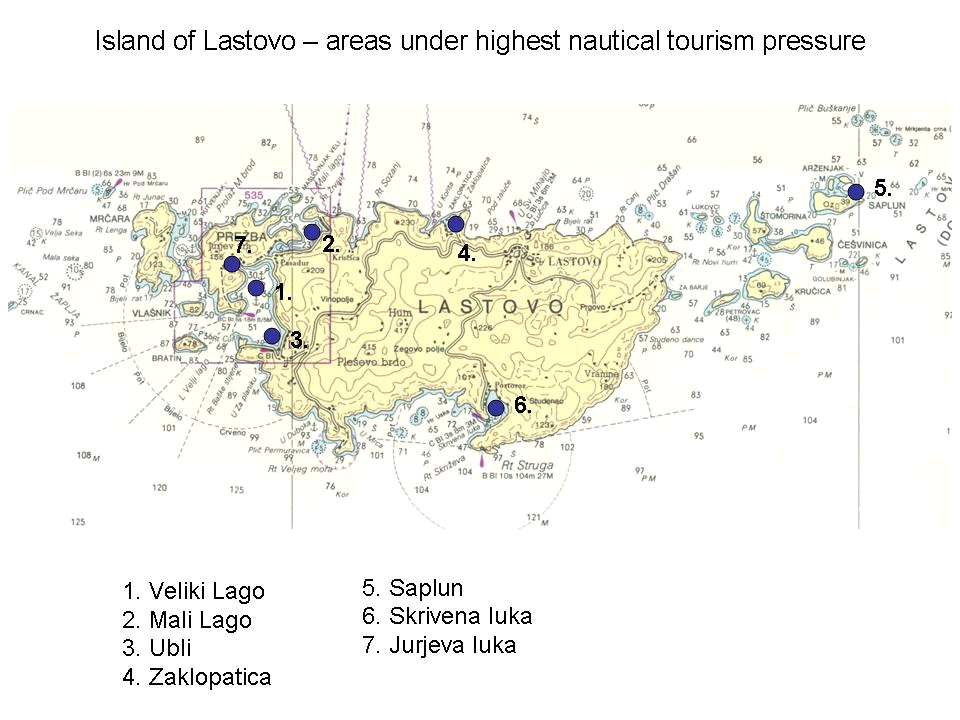

An increasing number of visitors arrive to the Lastovo Islands by yacht, using a number of very small private marinas and moorings, most of which lack legal concessions. However, these moorings provide a safe place for yachts and actually lower the incidence of “free” anchoring, so they are tolerated by the local government. Unregulated anchoring is practiced in almost all bays and coves, with damaging effects on the seabed, habitats and species. It also contributes to the spreading of invasive marine species (Figure 12). Oil and wastewater discharge and littering from boats and yachts significantly contribute to sea pollution, which often happens in bays that are already under stress from the sewage waters from surrounding houses. Water quality for swimming is measured several times per year by the Ministry of Environment in places such as Sv. Mihovil, Rt Zaglav, Skrivena luka, and Kupalište Pasadur, and these results still show high sea quality, though in the summer months the measurements also show a decline in suitability for bathing (Figure 13).

Figure 12: Invasive marine green algae Caulerpa racemosa – distribution map, (Source: Z.Jakl)

Although the Islands have very transparent seawater, rich marine life, and some of the best diving locations in the Adriatic Sea, scuba-diving is not well developed. This is due to the Island’s distance from the mainland and a lack of promotion within diving tourism groups. Until 2009 there was only one diving centre on Lastovo Island. Now there are two and it is expected that more of them will be opened. Most restaurants, apartments and hotels furthermore, are located along the coastline in small villages that have been constructed in the recent years. Some of them are constructed illegally or with high impacts on the landscape because of their proximity to the sea or their height which is often incompatible with the local landscape. Rows of houses are frequently built parallel to the narrow stretches of coast, separated by the main road and constructed in an unorganised manner. Such coastal development of apartments, moorings and hotels can be expected to continue in the future. The ancient main village, Lastovo, based in the centre of the main island offers interesting architecture but very little accommodation facilities. Here properties can belong up to ten or fifteen owners, many of which now live in America or Australia or are dead with legally unresolved succession issues.

Figure 13: Lastovo Islands NP – areas under highest nautical tourism pressure (Source: Z. Jakl)

Where these problems have been resolved, people have begun to rebuild and rent many of these properties. However, as of February 2009, foreigners were permitted to buy Croatian property without restrictions, so an increasing number of properties are being sold to outsiders. These are usually old people, who live in the Lastovo Islands only during the summer and therefore do not contribute to the development of the local economy, social life or maintenance of traditions.

.

6. The Protected Area (PA) Management System

The Nature Protection Act (Official gazette 70/05) regulates the system of protection and integrated conservation of nature and its assets. In Croatia there are nine categories of PA: Strict Nature Reserve, National Park, Special Nature Reserve, Nature Park, Regional Park, Nature Monument, Important Landscape, Forest Park, and Park Architecture Monument. PAs cover 5.85% of the national territory: equalling 9.01% of terrestrial surface but only 0.07% of territorial waters. National Parks and Nature Parks are managed at the national level by specific institutions based in or near PAs, while all other categories are managed at county or local levels.

The most important document for the management of PAs is the management plan, which defines the organization, usage and protection of space in national and nature parks for a period of 10 years, and legally provides opportunities for public participation. Management plans are developed by the PA management institutions and adopted by PA management boards after their evaluation by the State Institute for Nature Protection (SINP) and approval by the Ministry of Culture (MoC). Each park also has a Rule Book of Internal Regulations defining more detailed protection measures for each PA.

Since PA physical plans are approved by Croatian Parliament, these documents have the highest rank in the planning process hierarchy. However, while PA management is under the competence of the Ministry of Culture (MoC), physical and spatial planning are under the competence of the Ministry of Environmental Protection, Physical Planning and Construction (MoEPPPC). Physical and spatial planning in Croatia are furthermore very complex, usually entailing high levels of political influence. Moreover, Croatian laws are in a process of changing to fall in line with EU accession requirements. These combined situations often open legal gaps that allow the implementation of projects with high environmental impacts.

In general in Croatia processes of involving stakeholders in planning, decision making and management are still on the whole, undeveloped. Neither government nor citizens have had much experience in communicating on such levels due to the country’s communist history, throughout which all decisions were taken by the central government. However, public participation has recently begun to improve, mainly under the influence of EU accession processes.

.

6.1. Management of the Lastovo Islands NP and the role of stakeholders

6.1.1. Plans and Regulations

The establishment of the Lastovo Islands NP was based on the assessment of scientific data (species richness, habitats, cultural heritage, expected impacts on the local economy) and in consultation with local communities. It is managed by the Lastovo Islands Nature Park Public Institution, set up only in 2007 as previously mentioned. Operating from Lastovo Island and funded by the central government, it has only five employees (a Director, a Conservation Manager and three Rangers) equipped with only one boat. Furthermore, the regulations and physical plans of the Lastovo Islands Nature Park PA are still under development. The Spatial Plan for the NP, the responsibility of the MoEPPPC and the most important document in the planning hierarchy is still not ready, while the Dubrovnik-Neretva County Spatial Plan has been in place since 2003. The Lastovo Municipality Spatial Plan meanwhile is in the final stages of approval and expected to be in place by the end of 2009.

In addition, the Rulebook on Internal Regulations for the Lastovo Islands NP is still being drafted. The Rulebook will limit the quantity and type of fishing gear in the NP, the number of annual licences issued, and will define criteria for determining who can obtain licences. It will also divide the Islands into four fishing zones and every three years two zones will be closed for fishing. Spear fishing will be restricted to several particular areas of the park, and anchoring will be limited as well. Clearly, the entire planning process is complex in Lastovo and has suffered delays for over 4 years due to politics and slow bureaucracy. In the absence of effective regulation a great deal of illegal construction (including that of nautical moorings) has therefore been tolerated.

.

6.1.2. Stakeholder Participation

In response, the Lastovo Islands Nature Park Public Institution has initiated the development of a management plan under the MedPAN South framework. This is an international pilot project that aims at supporting 5 Croatian marine PAs (including Lastovo Islands) in developing management plans, networking and exchanging experiences. In Croatia this project is being implemented by the authors of this chapter, Association Sunce and coordinated by the WWF, the Ministry of Culture and the State Institute for Nature Protection. The PA status of the NP only allows economic activities which do not pose significant threats to the values due to which the area is protected. This means that in practice protection has to be negotiated amongst stakeholders, of which there are many.

The main actors in the Lastovo Islands NP are the Ministry of Culture (responsible for nature protection), the State Institute for Nature Protection, the Ministry of Environmental Protection, Physical Planning and Construction, Public Institution Nature Park Lastovo Islands, the Lastovo Municipality, professional, small-scale and recreational fishermen, tourism sector representatives (nautical tourists, restaurant owners, accommodation facilities owners, mooring owners, tourists, etc.) and national/international NGOs (Sunce, WWF). Another important actor is the Croatian Ministry of Defence which holds the property rights of many of the old military facilities on Lastovo Island, some of which are based in very attractive areas for tourism development.

Communication, participation and co-management are seen as the way to manage PAs in Croatia since most of these areas have communities living within their borders in possession of private property. Local people cannot simply be forced to obey rules; they need to have a sense of ownership over the PA and believe that these regulations can bring good to them and the environment they live in. In engaging with stakeholders, different values and interests come into play. Social multi-criteria evaluation (see below) could be very useful in facilitating participatory decision making on the future management of the Lastovo Islands NP.

.

7. The Future of Nautical tourism development

Coastal areas in Croatia are suffering devastation from illegal and poorly planned construction and development in general. The development of nautical tourism generates additional pressure on coastal resources, especially in PAs which are the most attractive areas for nautical tourists. The Kornati National Park and its surrounding area, for example, are considered one of nautical tourism’s “paradises”, visited by around 20 000 boats per year, which implies the throwing of as many anchors and much damage to the sea bed. The Kornati National Park Public Institution tried to install buoys to stop anchoring and allow safer mooring for nautical tourists but was forced by the Ministry of Culture to remove them as they were not in line with the current physical plan. Developed independently of the Institution, MoC planning foresees that in the next 10-15 years all individual visits to the park will be stopped, eliminating the need for a system of buoys. Meanwhile, the number of nautical tourists in the park is increasing each year and destruction of the sea bed continues.

In 2008 the Public Institution Lastovo Islands NP started charging entrance fees of 2.70€ per person per day. In 2008, 20 570 entrance tickets were sold. This fee is currently charged only to nautical tourists but will likely soon apply to all visitors. This practice is already implemented in almost all Croatian PAs and is largely driven by the Ministry of Culture and the central government. The objectives are to lower the costs for financing protection from the State budget, to ensure the self-sustainability of the park and the local economy, to obtain information about the number of visitors, and to increase awareness about the fact they are in a PA. Unfortunately, although the money stays in the Public Institution, often the priority for using this money is to promote further tourism while the implementation of conservation measures comes last. In the case of The Lastovo Islands NP, the large number of islands and islets has meant that money collected from entrance fees has mainly been spent by the Public Institution on funding boat maintenance and petrol costs for monitoring. The salient point to be made here, however, is that because PAs are mainly protected through entrance fees, managers are keen to increase the number of visitors (rather than simply raise entrance fees, which are already seen as relatively high) regardless of the pressures on habitats.

It is not surprising then that a large proportion of the local community of the Lastovo Islands NP does not welcome the use of entrance fees since the Park is currently not offering any services in return or contributing to systematic forms of protection (buoys systems, facilities for collecting waste and waste-waters from yachts). They believe that the Public Institution should invest money in conservation and more importantly, provide clear information and include locals, who are very sceptical about what the fees will be spent on, in management planning. The owners of restaurants earning a living from nautical tourists are also apprehensive about entrance fees, fearing their implementation will lead to a decrease in the number of visitors without contributing to environmental protection and a positive experience for visitors.

Meanwhile, plans are being developed to forbid anchoring on all of Lastovo Island and to restrict mooring to specific locations. In these specified areas the total maximum number of boats per bay was set by the Municipal Physical Plan, but without being preceded by the necessary studies. Studies on mooring capacities of each bay and cove are needed before project implementation, as are detailed plans for implementation of the mooring system, i.e. whether it will involve fixed moorings, marinas, buoys, and/or pontoons (Table 7). The situation is similar for new construction projects, particularly those of the new tourist zones foreseen in the Island’s Municipal Physical Plan. The physical plan sets up construction zones and the maximum possible construction capacity while interested investors and environmental and nature impact assessment studies define this in more detail.

Table 7: Moorings and harbour capacities (Source: (Draft) Lastovo Municipality Physical Plan, 2007)

| Moorings | ||||||

| Area | Maximum planned moorings | Existing moorings | Surface (approx) | Already constructed area | Maximum depth (approx) | |

| Lučica* | 10 | yes | 0.17 ha | yes | 5 m | |

| Pasadur* | 70 | yes | 6 ha | yes | 6 m | |

| Sv. Mihovil* | 10 | yes | 0.47 ha | yes, some | 5 m | |

| Ubli* | 50 | yes | n/a | yes, ferry port | 10 m | |

| Zaklopatica* | 40 | yes | 8 ha | yes | 12 m | |

| Skrivena luka** | 80 | yes | 20 ha | yes | 17 m | |

| Mrčara | 10 | yes | n/a | yes, some | 7 m | |

| Kremena** | 60 | 0 | 6,5 ha | no | 34 m | |

| Saplun | 30 (anchoring buoys) | no | 13 ha | no | 30 m | |

| Jurjeva luka | 200 (support for planned tourist facilities) | no | 6 ha | yes, old military area | 10 m | |

| Nautical tourism harbours (marina) | ||||||

| Kremena | 400 | no | 6.5 ha | no | 34 m | |

| Skrivena luka | 200 | yes | 20 ha | yes | 17 m | |

|

*Harbours of local importance (for local community)

**After development of the nautical tourism harbour, moorings will become part of marina |

||||||

.

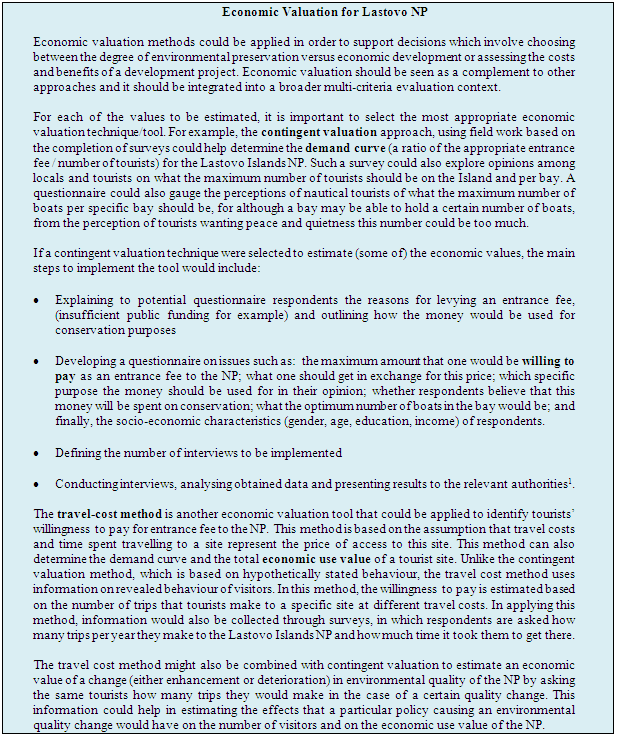

Therefore, a mix of policy measures may be of interest. There are a variety of economic instruments for tourism that could be effective, including regulatory or “command and control” instruments (such as the prohibition of anchoring, urban zoning, or fishing quotas), institutional instruments (introducing nautical tourism eco-labels, or changes in property rights like privatization of military facilities which could be reformed for tourism purposes) and market based instruments (like levying an environmental tax or a user fee for raising funds for conservation of the NP, or creating financial incentives for sustainable tourism practices). A higher entrance fee, if locals could be persuaded in its favour, could for instance reduce the number of visitors and consequent impacts (depending on the response, or “elasticity” of demand to changes in price – see below), if the receipts are not spent on tourism marketing.

The scale of construction that will ultimately be implemented will depend on local communities’ vision of the future, potential investors, and the strength of Croatian laws. It is important that the Lastovo Islands NP keeps both small-scale and high-quality tourism in order not to deteriorate its offer of environmental services that is currently attracting tourists and which distinguishes it from the other parts of Croatia. There can be an alternative to mass and high-impact tourism, and this can be achieved in practice with the NGO community as a watch-dog to ensure laws are implemented and nature is respected.

Learning from the Kornati National Park experience, the Lastovo municipality and Public Institution of the Nature Park are working to ensure via the Rule Book on Internal Regulations that the management authority can control anchoring by limiting anchoring and mooring to specific locations, while the Municipal Physical Plan sets a limited maximum number of boats per location (in line with the County Physical Plan). Moorings can be organised directly by the Public Institution or by other parties through a system of concessions granted by the Dubrovnik-Neretva County, which contain very general requirements regarding environmental protection.

All interested parties agree that anchoring and mooring should be limited and the majority agrees on the chosen locations. The issues of the maximum number of boats per location, the method of mooring (marina, buoys, and pontoons) and charging of entrance fees have, on the other hand, aroused controversy and remain to be decided. Some of the conflicts are arising between restaurant and mooring facility owners, who would like more nautical tourists and who think that entrance fees are discouraging tourists to visit the Islands, and the people who rent apartments and think that boats are polluting the sea and disturbing swimmers. It is the method of mooring organisation however that will play an essential role in determining the level of new construction and of the permanent impact of tourism on the landscape and the environment.

.

8. Conclusions: The CSO vision

Tourism development can create considerable benefits for the local economy in the long run. The Sunce vision for maximising these benefits with minimal environmental impact is one in which boats visiting the Islands would be predominantly moored to fixed buoys distributed across selected coves and bays. The number and distribution of buoys would be based on a carrying capacity estimation (See below), and a system discouraging anchoring would be in place and supported by the local community (e.g. those that are anchored would pay much higher entrance fees). The system of buoys would also be designed to have a low impact on the surrounding environment and landscape. The notion of carrying capacity combined with an assessment of the area’s resilience (the ability of the system to recover when disturbed) could contribute significantly toward reaching agreement on the appropriate number of nautical tourists for Lastovo NP.

Resilience is an approach for ascertaining which parts of the ecosystem will give way to pressures first, as it measures the ability of an ecosystem to absorb shocks while maintaining its functionality. When change occurs, resilience provides the components for renewal and reorganisation. Vulnerability is the flip side of resilience: when a social or an ecological system loses resilience it becomes vulnerable to change that previously could have been absorbed. In a resilient system, change has the potential to create opportunity for development, novelty and innovation. This can happen after forest fires in the Mediterranean (although perhaps not on southern Lastovo where Aleppo Pine is thriving at the expense of Holm Oak, acidifying the soil, negatively impacting biodiversity and increasing the risk of future forest fires), but in vulnerable systems even small changes may be devastating, as is often the case with fisheries and coral extraction. With assessments of the carrying capacity and resilience of the area, it would then be possible to study nautical tourists’ willingness to pay to use moorings. This could be translated into higher entrance fees, which ideally would be recycled into environmental investments.

A number of new high-quality tourist accommodation facilities would be constructed in areas previously devastated by military bases. Several new fixed coastal mooring areas would be developed, but limited in number according to carrying capacity. New moorings and new accommodation facilities providing additional beds would be constructed respecting the local environment, culture and architecture. The construction of these facilities would significantly contribute to local infrastructure development, especially waste and waste-water management. Money collected from entrance fees would be transparently reinvested into furthering the conservation system. A trust fund to subsidize green technologies would be implemented, partially funded through entrance fees. The Public Institution of the Lastovo Islands Nature Park would have enough financing and capacity to run the management of the area properly, a task which would be much easier with the involvement of locals in decision making.

No-take zones supporting fish stock restoration would be set in place in consultation with local stakeholders. These areas would not only revive depleted populations of fish through spill-over effects (increases of fish populations outside no-take zones) but also attract a substantial number of divers eager to see untouched nature and a diversity of fish species in their natural environment. Professional fishing would be limited by restricting the number and type of tools, issuing fewer licences which would be offered mainly to locals, and sport/recreational fishing would be restricted to a few specific zones. Illegal fishing would cease to be a problem as the attitudes of local communities changed and law enforcement improved. Tourists would have the opportunity to enjoy the Islands’ beauty, not only along the coastline, but also inland, discovering fields, architecture, and folklore. Good local food, natural and cultural excursions and events would attract yachts and younger generations would have opportunities to run businesses, reversing trends of depopulation.

This is the vision of the CSO Sunce, one of the stakeholders of the Islands. A shared vision of all stakeholders will have to be defined through a participatory process. In order to move toward the vision described above, in which the economic benefits of tourism are increased and equitably distributed with minimal environmental impact, it will essential to develop and implement a strategy focused on forms of tourism that will create economic added value while preserving the environment on which these activities depend.

.

- “A quick scan of the potential for sustainable tourism development of the island of Lastovo”, Commissioned by Opcina Lastovo (community Lastovo); First draft 24-12-04; Niek Beunders MA Senior Lecturer and Consultant, Centre for Sustainable Tourism and Transport (CSTT), Breda University of Professional Education, Breda, the Netherlands.

- “The Dalmatian Conservation Action Plan”, 2006, WWF, Association Sunce.

- “Joining Forces for Sustainable Tourism”, 2006, WWF; Tour operators initiative for Sustainable Tourism. Workshop report.

- “Croatian Tourism Development by 2010” Final Version, Republic of Croatia, Ministry of tourism, strategy report.

- “Croatia Nautical Tourism Development Study, 2004, Croatian Hydrographic Institute, Ministry of Sea, Tourism, Transport and Development

- “Republic of Croatia Nautical Tourism Development Strategy (2009.-2019.), 2008., Ministry of Sea, Transportation and Infrastructure, Ministry of Tourism

- Nature Protection Act (Official gazette 70/05)

- „Park Prirode Lastovsko otocje – Strucna podloga za zastitu“, 2005, Drzavni zavod za zastitu prirode.

- Temeljna ekološka studija uvale Telašcica, 2008, Ruđer Bošković Institute