5. The ‘Dematerialization’ of Consumption?

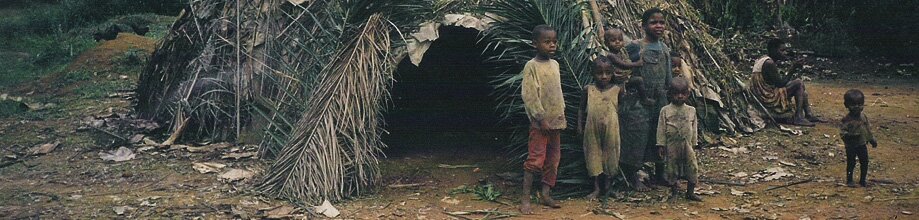

In economic theories of production and consumption, compensation and substitution reign supreme. Not so in ecological economics, where diverse standards of value are deployed ‘to take Nature into account’ (O’Connor and Spash 1999). In the ecological economics theory of consumption, some goods are more important and cannot be substituted by other goods (economists call this a ‘lexicographic’ order of preferences). Thus, no other good can substitute or compensate for the minimum amount of endosomatic energy necessary for human life. This does not imply a biological view of human needs; on the contrary, the human species exhibits enormous intraspecific socially caused differences in the use of exosomatic energy. To call either the endosomatic consumption of 1,500 or 2,000 kcal or the exosomatic use of 100,000 or 200,000 kcal per person/day a ‘socially constructed need, or want would leave aside the ecological explanations and/or implications of such a use of energy. Similarly, to call the daily endosomatic consumption of 1,500 or 2,000 kcal a ‘revealed preference’ would betray the conventional economist’s metaphysical viewpoint.

There is another approach which, as pointed out by John Gowdy, builds upon the ‘principle of irreducibility’ of needs. This idea was proclaimed by Georgescu-Roegen in the previous edition of the Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, article on ‘Utility’. According to Max-Neef (Ekins and Max-Neef 1992) all humans have the same needs, described as ‘subsistence,’ ‘affection,’ ‘protection,’ ‘understanding,’ ‘participation,’ ‘leisure,’ ‘creation,’ ‘identity,’ ‘freedom’; and there is no generalized principle of substitution among them. Such needs can be satisfied by a variety of ‘satisfactors.’

Instead of taking the economic services as given, as in MIPS (passenger per km, square metres of living space), we may ask why there is so much travel, why so much building of houses with new materials instead of the restoration of old ones, and so on. In the late 1990s research was undertaken on the following question: is there a trend to use ‘satisfactors’ that are increasingly intensive in energy and materials, in order to satisfy predominantly nonmaterial needs? (Jackson and Marks 1999). The expectation that an economy that has less industry will be less resource intensive is perhaps premature. Input–output analysis of household lifestyles (by Faye Duchin and other authors) shows the high material and energy requirements of the consumption patterns of many of those employed in the postindustrial sector.

1. Origins

2. Scope

3. Disputes on Value Standards

4. Environmental Indexes of (Un)sustainability

5. The ‘Dematerialization’ of Consumption?

6. Carrying Capacity and Neo-Malthusianism

7. Final Remarks on Transdisciplinarity

References