Local Governance and Environment Investments in Hiware Bazar, India

Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), India

Author: Supriya Singh

Download case study as pdf-file.

2. Background: Water Scarcity in Ahmednagar, Maharashtra

3. Hiware Bazar and its People

4. The Beginning of the Success Story

.

.

.

Hiware Bazar is a village that has achieved success through investing in local ecology for economic good. The village followed an integrated model of development with water conservation as its core. It won the National Water Award for its efforts in water conservation and raising village productivity levels.

The village is outstanding because:

- It uses water as the core of village development

- It is community driven

- Its village-level resources planning is impeccable

- It uses government programmes but with community at the driving seat

- And it has thought out its future plans to make the initiative sustainable

This case study examines the keys to the success of Hiware Bazar with a view to identifying the potential for replication across region and country.

Key words: Environmental investments, rural poverty, water governance, grazing rights, forest management, crop pattern, collective decision-making, community resource management, water harvesting, national rural employment guarantee act, institutional innovations, property rights, virtual water, biogas, livelihood security.

.

2. Background: Water Scarcity in Ahmednagar, Maharashtra

In the Ahmednagar district of Maharashtra State, the village of Hiware Bazar is located around 17 km west of the town of Ahmednagar (see Figure 1). The district is the largest in the state and exhibits contrasting living conditions within it. The north of the district is prosperous with sugarcane cultivation and a large number of co-operative sugar factories. This part is canal irrigated and economically better off, while the southern half of the district features rain-fed farming and limited agricultural activity. This has lead to the out-migration of people in large numbers for work in other parts of the district as well as outside of it.

Figure 1: Hiware Bazar, Ahmednagar, Maharashtra

.

The district lies in the Maharashtra plateau, with a mix of flat agricultural land and undulating terrain. In most seasons, the hills are bare and dry. Farmers survive mainly on groundwater and levels are declining. Rainfall is variable and drought common. Even in years when rains have been bountiful water has been scarce. The average rainfall is around 400-500 mm, but its persistent failure is what breaks the district’s back—there have been three consecutive years of drought from 2001 – 2003. Furthermore, the terrain in the district is undulating and there are pockets of hard impervious rock spread across the area making access to groundwater difficult.

The property rights regime in the area, as in much of the rest of the country promotes over-extraction of water. Groundwater as a resource belongs to anyone who owns the piece of land from where the water is drawn. Water as a resource is ‘free’ as this regime calls for no control over use of water. At the same time, the issue of groundwater recharge is left to nature and is not generally seen as necessary for people to manage. The countryside is therefore perforated with hand pumps, tube wells and bore wells to quench the thirst of people and agriculture. Statistics show that 80-90% of the irrigated area in the country still sources its supply from groundwater. In addition, 80% of drinking water supply in the country is also sourced from groundwater resources. This means that massive utilisation without ascertainment of the resource’s recharge has led to water scarcity across the country.

State response to the shortage of water has been varied, with investment in recharge programmes like watershed development schemes and even employment generation schemes to fund rainwater harvesting across villages. The Employment Guarantee Scheme (EGS) of Maharashtra was one such scheme rolled out to provide relief during drought conditions in the early 1970s. The scheme offers each rural person 100 days of paid labour a year to work on rural development works. In 1972, when the state was hit with crippling drought and mass migration, it implemented this scheme by which professionals working in the cities would pay for employment in the villages. This employment was guaranteed by law, which meant it provided an entitlement and put a floor to poverty. Since work was available locally, people did not have to flee to cities. It later formed the basis for the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme introduced across the country in 2006. This scheme focuses specifically on water harvesting. The idea again is to create jobs for people locally so as to reduce distress migration and also provide for their long-term future in the bargain.

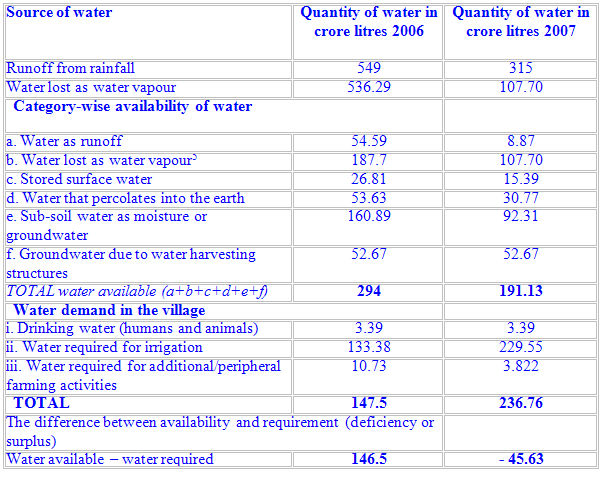

Figure 2: Water, Jobs and Soil

Figure 2: Water, Jobs and Soil

.

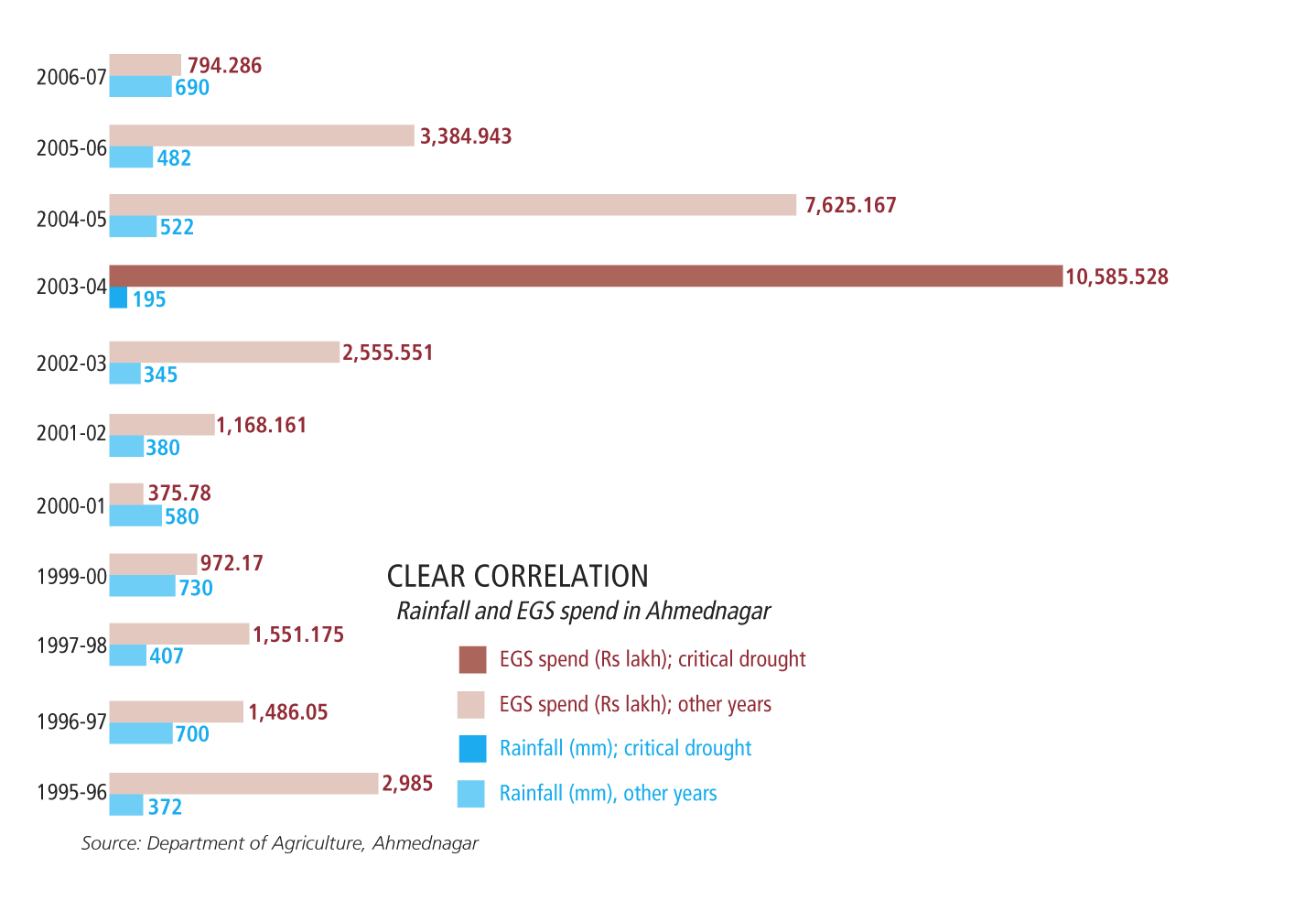

In the Ahmednagar district there was a clear correlation between the intensity of drought and State spending under the EGS on watershed work and soil conservation (see Figure 2: Water, Jobs and Soil). In 2003-04, the critical drought year, spending shot up to almost 1060 million Rupees (Rs) [There exchange is approximately 60 rupees to the euro.], a big chunk of the total of Rs 3380 million spent between 1995-96 and 2006-07. This Rs 1060 million went towards making 201 farm ponds, doing 20 000 ha of continuous contour trenching, another 3,400 ha of compartment bunding and building over 1000 check dam-like structures in different streams and drains to improve water harvesting. In this period the district built over 70 000 water-harvesting structures. In addition, it treated, through trenching and field bunding, another 190 000 ha. Of the district’s area of just over 1.7 million ha, roughly 11 per cent was treated for soil conservation. “We have in these years of scarcity used funds to plan for relief against drought,” says Vikas Patil, Director of the district’s Department of Agriculture (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Ridge to Valley

Figure 3: Ridge to Valley

.

The impact has been tangible, say officials, citing three indicators. First, there has been a drastic decline in the demand for employment in the last few average and high rainfall years. In 2006, the district spent as little as Rs 7 crore [One Crore = 100 Lakhs, One lakh = 100000] on building water structures. “No one is ready to work on our public employment programmes. This is because agriculture is booming and labour is short,” says Uttam Rao Karpe, the Chief Executive Officer of the district’s Zilla Parishad (District Rural Development Agency, DRDA). In that year, he says, nearly Rs 500 million of the funds for soil and water conservation lay unspent. A look at the employment demand statistics shows that from April-December, 2007, only 7000 households demanded work, as compared to the 30 000-odd who did so in 2006-07 under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA). With improved water availability, people prefer to work on their own fields. An added effect has been felt on the wages in the area. The average wages in the district have risen from Rs 40 to an average of more than Rs 70 [government figures taken from the nrega.nic.in website]. With the revival of agriculture, opportunities to work within the village have increased, as have other employment opportunities in small-scale industry.

Secondly, the area under cultivation has increased, farmers have moved to cash crops and yields have risen. “Agriculture has become productive and lucrative,” says Karpe. The best indicator is the fact that previously, during drought there was a desperate shortage of fodder and farmers preferred not to sell sugarcane but to use it as fodder, but now there is surplus of sugarcane in the district, according to officials.

Thirdly, and key, is the improvement in the water table of the district because of soil and water conservation. In the district, roughly 20% of the 1.2 million ha of cultivated land is irrigated. But the bulk of this—75%—is well irrigated. Farmers use dug wells, which tap the shallow aquifers, and increasingly deeper and deeper tube wells for cultivation. The district groundwater authorities monitor 200 wells to check water levels. Their data shows, on average, there has been a 5-metre rise in water levels between the peak drought period of 2003 and 2007. Analysis of individual wells across different watersheds confirms this trend. The groundwater department now declares that less than average rainfall is no longer a problem in the area. Even with less rainfall, the water harvesting structures are likely to hold water and therefore have a stabilising effect on the groundwater table.

One key challenge in the future will be to improve productivity, with use of techniques to minimize water use and change cropping patterns. “The district administration is promoting drip irrigation to counter the increasing use of borewells,” says Patil. The drip irrigation techniques in use across the countryside are low energy systems that save up to 70% of the energy costs compared to flood irrigation systems. Another big challenge, say officials, is to protect watersheds—mostly lands under the forest department. “Till now we have mainly worked in the storage zone and recharge zone, not in the upper areas of the watershed,” says Ajay Karve, Deputy Director of the district’s Groundwater Department. “The next phase needs to focus on runoff or hill areas,” suggests Karve. This will ensure the district is drought-proofed. The message from Ahmednagar is clear: if we can create productive assets then drought relief can become drought-proofing.

.

3. Hiware Bazar and its People

The village of Hiware Bazar is fairly representative of the uncertain conditions in the area but stands out as a paragon of successful community resource management. Spread over an area of 976 ha, 70 ha is forested, 860 ha is private, and 8.5 ha is Panchayat land. The community is more or less homogenous with most of the population belonging to upper caste Marathas and only two Scheduled Caste families in the village. Agriculture forms the mainstay of the local economy along with animal husbandry. Prior to the water conservation works in the village there was rampant poverty and small-scale industries like brick making and liquor shops dotted the landscape. The brick making industry uses the most fertile topsoil to make bricks leaving large stretches barren and useless. To add to the woes, brick making consumes a large quantity of water, adding to the already existing shortage.

Due to the vagaries of the monsoon season, agriculture was poor and there was large-scale outmigration. The monsoon by its very nature is highly erratic, and with the village receiving a scant 400mm rainfall in good monsoon years, water was always scarce. Back in the 1970s the village, famous for its un-putdownable “Hind-Kesari” wrestlers, lost a crucial fight against ecological degradation. The village slipped into an abyss of ecological degradation with deforestation in the surrounding hills, the catchment areas of the village. During the monsoons, the run-off water from the hills looked stark brown, says Chattar, a native of the village. “Naked hills shocked the elders in the village. The same hills were once home to mogra flowers and fruit trees,” remembers Arjun Pawar, the Sarpanch of the village from 1975 to 1980. It made drought chronic and acute as even a slight deviation in rainfall resulted in severe crop failure. The village faced acute water crisis and severe land degradation. The village’s traditional water storage systems were in ruins.

People migrated in hordes due to constant crop failures and drought. By the early 1980s as many as 50% of the village population had drifted out of the village. During 1989-90, less than 12% of the cultivable land was under cultivation. The village’s wells used to have water only during the rainy season. In 1972, when water scarcity hit the state, a percolation dam was built using EGS funds. The village took to making, drinking and selling country liquor. Those who were left behind further cleared the dwindling forest for survival. It worsened the village economy further. Families began to shift out, first seasonally, and then permanently to big cities like Pune and Mumbai. “Even government officials shifted out and soon Hiware Bazar became a punishment posting,” recalls Maruti Thange, a 56 year-old local farmer. Shankuntla Pandurang Sambole, a 50 year-old female resident, recalls the days when water was unavailable in the village. “I abandoned farming my seven acres of land in the early 1990s and became an agricultural labourer on a big landlord’s farm earning Rs 40 a day”.

Contrasting the past with the present is inspiring. Of the village’s 216 families, 25% are millionaires, earning more than a million rupees in profit per annum from agriculture and dairy farming alone. On average, every village resident earns twice the average of the top 10% of the earning population in rural areas. In the last 15 years the average income has been multiplied by 20. The forest here is well preserved; the fields are green and the residents happy. Shankuntla has bought an additional four acres of land and grows tomatoes and onions. Today she earns around Rs 100 a day from vegetable selling alone.

How did the village script such an economic miracle? It attained this feat by using EGS money for the regeneration of the village ecology: the land and water that sustains close to 90% of the residents. It turned its crisis into an opportunity by channeling government drought money into the creation of productive village assets like water conservation structures and reforestation to restore the village ecology. “Living in the rain shadow area with less than 400 mm of rainfall per annum has its blessings, only when you know how to manage the water”, says Popat Rao Pawar, Sarpanch of Hiware Bazar. The village’s message lies in the importance of the means as well as the ends. The village story is in contrast to the norm where villages that get money under EGS usually follow whatever they are told by the government or implementing agency. There is no organised effort on the part of the villagers to scope for the requirements and act accordingly. This is where Hiware scores.

.

4. The Beginning of the Success Story

In the 1980s, the youth of Hiware Bazar began to think about remedying the dejectable scenario confronting them. The elections to local Panchayats in 1989 provided the right occasion. In search of a candidate who would be acceptable to all factions, the village youth zeroed in on Pawar, who won unopposed. From here began the village’s tryst with destiny. Inspired by social activist Anna Hazare, Pawar took up water conservation works year after year.

Anna Hazare is a Gandhian who scripted the success story for his village Ralegaon Siddi, 40 km from Hiware Bazar, in much the same way as Hiware. He too inspired his people to come together and treat the land so as to harness rainwater and put social rules in place to manage the natural resources. His model of development using water as the core and the consequent success of Ralegaon has been an inspiration, not only to Hiware Bazar but also to a large number of other villages across the country. Even government programmes have been inspired by the success to re-emphasize watershed development as a way of holistic natural resource management.

The district was brought under the Joint Forest Management (JFM) Programme in 1992. The JFM programme itself was born in 1988 after a law was passed by the central government to include communities in the conservation of forest resources, mainly village forests. By the year 1993, the district’s Social Forestry Department reached Hiware and brought Pawar on board to regenerate the completely degraded 70 ha of village forest and the catchments of the village wells. With local labour donations, the Panchayat built 40,000 contour trenches around the hills to conserve rainwater and recharge groundwater. Residents took up massive plantation and forest regeneration activities. Immediately after the monsoon, many wells in the village collected enough water to increase the irrigation area from 20 ha to 70 ha in 1993. “The village was just beginning to get a bit of life back in its veins,” remembers Pawar.

Hiware Bazar’s achievement under the JFM programme is special as it counts among the few successful JFM cases in India. JFM as a programme failed to capture the imagination of the people mainly due to unclear property rights and weak institutional capacities. For any programme to be successful therefore one needs a clear property rights regime, whether defining communal or individual rights, strong institutional support as well as a strong and visionary leadership.

In 1994, the residents, along with the Gram Sabha (village council), approached 12 different agencies to implement watershed works under the state’s EGS. The village prepared its own five-year plan for 1995-2000 that emphasized local ecological regeneration. Implementation of the five-year plan then became the objective of the EGS, which was otherwise a wage employment programme. This was to ensure that all departments implementing projects in the village would have a common and integrated work plan. Work began in 1995 building contour trenches across the village hillocks and planting trees to arrest runoff.

Simultaneously, in 1994 the Maharashtra government brought Hiware Bazar under the Adarsh Gaon Yojana (AGY), a scheme to replicate the success story of Ralegan Siddhi. The AGY programme was based on five principles: a ban on cutting trees, free grazing, and liquor; family planning; and contributing village labour for development works. The first work it took up was to plant trees on forestland and people were persuaded to stop grazing in these lands.

Grazing forms the second most important part of rural-pastoral life with every household owning cattle. Traditionally, common land in the village also doubles as grazing ground. For watershed development to be effective this activity had to be stopped to allow the pasture to regenerate. In Hiware Bazar, prior to the implementation of the AGY rules, many people owned more goats than cows. Goats eat plants by pulling them out causing the soil to loosen and leave less scope for the plants/grasses to grow back. Keeping this in mind, the village slowly sold off all its goats in favour of cows.

The village invested all its development money of the five-year plan on water conservation — recharging groundwater as well as creating surface storage systems. It laid a tight trap to catch rainwater. The 70 ha of forest helped in treating the catchments for most of the wells, 414 ha of contour bunding stopped run-off and saved farms from silting, and around 660 water harvesting structures of various types captured rainwater. A total of Rs 42 Lakhs [1 Lakh = 10 000 Rupees] was spent thought the State government on EGS in the village. Treating 1000 ha of land, the per ha cost of treatment of land was Rs 4000. But the cost benefits in term of raised incomes of village residents were phenomenal.

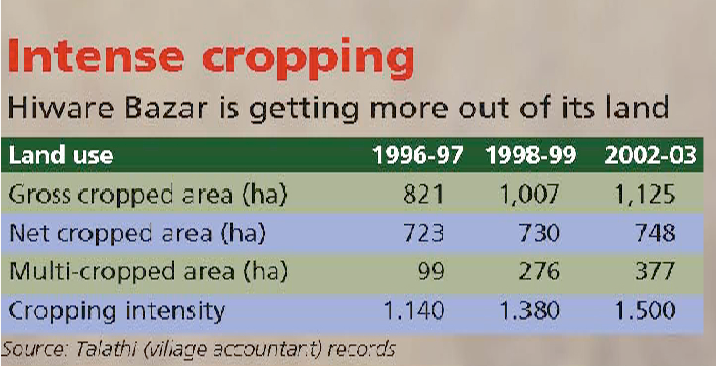

The village today stands on its own, reaping benefits from the investments it made in conserving water and in drought-proofing the village. “The little rainfall it receives is trapped and stored in the soil”, says Deepak Thange, who volunteered in the watershed works in the village. The economic harvests of water conservation have now translated into prosperity for the village. The number of wells has increased from 97 to 217. Land under irrigation has gone up from 120 ha in 1999 to 260 ha in 2006 (See Table 1).

Table 1: Intense Cropping in Hiware Bazar

.

Courtesy of the watershed works, grass production went up from 100 metric tonnes in 2000 to 6000 metric tonnes in 2004. Sakhubai Pandurang Thange, a 70-year-old resident who had been cutting grass for the last 25 years, recalled a time when grass scarcity had increased due to overgrazing. “The efforts put in by the people of the village for soil and water conservation have created surplus for us today,” says Sakhubai. Every morning from 7 am to 10 am for three months beginning in Dusshera (around the month of October), the grass-cutting season begins. Nearly 80 people from the village come to the forest area to collect the grass. A sum of Rs 100 per sickle has to be deposited with the Village Development Committee, says Sakhubai. Her son, Sambhaji Thange, a 28-year-old farmer, who accompanies her to collect the grass everyday, proudly states, “Residents of the nearby Bhuvre Patar village come here to collect grass and aspire to be like Hiware Bazar.” The people of the village understand the value of grass and hence stall-feeding is promoted in the entire village. In case of violations, the Village Development Committee levies fines.

The village makes an effort to share the increasing wealth equitably. The poor or landless who have been deprived of their customary rights to pasture land can buy grass-cutting rights from the Panchayat. An increase in the water table and the rules in place to protect the watershed have benefited everyone with higher availability of water and more employment opportunities for the landless in the village. There is no family in the village that feels excluded from the benefits incurred from the resource management regime in place. Furthermore, schemes for the landless and backward castes (though few in Hiware Bazar) are well implemented by the Panchayat. The village governing body also helps people monetarily if need be.

According to a household survey conducted in 1995, 168 families out of 180 were below the poverty line (BPL). The number of BPL families shrank to 53 in the survey conducted in 1998. There are now only three BPL families in Hiware Bazar out of 216. “There has been an unbelievable 73% reduction in poverty. This has been due to the profits earned through the dairy and cultivation of cash crops,” says Popat Pawar.

Local affluence definition

Hiware Bazar has set a very high standard for itself in terms of defining affluence. The village has developed its own set of BPL indicators for the village, which includes access to two meals a day, school enrolment of minimum two children in a household and expenditure on health. According to Pawar, the village poverty line is set at Rs 10 000 per year, the necessary level of spending on all three items. This is around two and a half times that of the official Government of India rural poverty line that stands at Rs 4380 per year. Despite this high benchmark,the number of BPL families is negligible. Another indicator of the village’s prosperity is that the village now has no demand for works under the NREGA since it has replaced the EGS.

.

Hiware Bazar’s strong and participatory institutional set up facilitated the initiatives. The Gram Sabha became the nodal institution, deciding everything from identifying the site for a water harvesting structure to sharing of water and types of crops to be taken up with consensus. The village voluntary organization became its implementing arm.

The village is not taking its turnaround lightly. The Gram Sabha continues to do judicious planning so that the ecological wealth generated doesn’t go to waste. Its biggest innovation is the water budget that it does annually (see box). The village’s second five-year plan (2000-2005) has focused on sustainable use of the regenerated wealth. As a part of it, every year the village takes stock of its water availability and dictates cropping patterns according to water availability. There are no violations. The village appoints two youths every year to take charge of vigilance activity and look into possible violations or any other problems and bring them to the notice of the Gram Sabha. The system has become efficient in managing itself as every member of the village is a potential watcher and the proceedings of the Gram Sabha are transparent. According to Habib, a resident of Hiware Bazar, “The essence of the experiment in watershed development comes from the strong Gram Sabha. It is here that decisions for the village are made. The greatest environmental planners are the village residents themselves and the institution of Gram Sabha empowers them to plan for themselves.” Every adult member of the village is automatically a member of the Gram Sabha. The Gram Sabha convenes once every month and may be asked to convene as and when required.

.

Since 2002, Hiware Bazar has been doing an annual budgeting of water assisted by the Ahmednagar districts’ groundwater department. Every year the village measures the total amount of water available in the village, estimates the uses and then prescribes the agricultural cropping to be taken up. All this is done through the instrument of Gram Sabha whose decisions are binding for the residents of the village. “It is through consensus that the village decides on the crops that are grown”, says Shivaji Thange, who works with the village watershed committee. The cropping pattern is undergoing a change in favour of cash crops but with high productivity and availability of water food crops produced in the village also suffice. Many families now buy food grains from the market. Food security will not be an issue for the village for a long time to come.

Through the five years of water budgeting, the village has been able to identify its average water availability. It is estimated that with 400 mm of rainfall, a small amount, the village of Hiware Bazar will have sufficient water throughout the year. Because the the village has an average shortfall of 50 to 80 million litres, the Gram Sabha has banned drilling of borewells for irrigation. “The discipline on this decision is maintained”, says Thange.

“The audit process begins with the monitoring of the groundwater level of the six observation wells identified in the village, along with the amount of total rainfall received measured by the village’s 3 rain gauges. The cumulative sum of rainfall and groundwater is the total water available to the village after monsoons,” explains Ramesh O. Bagmar, Assistant Geologist, Groundwater Department.

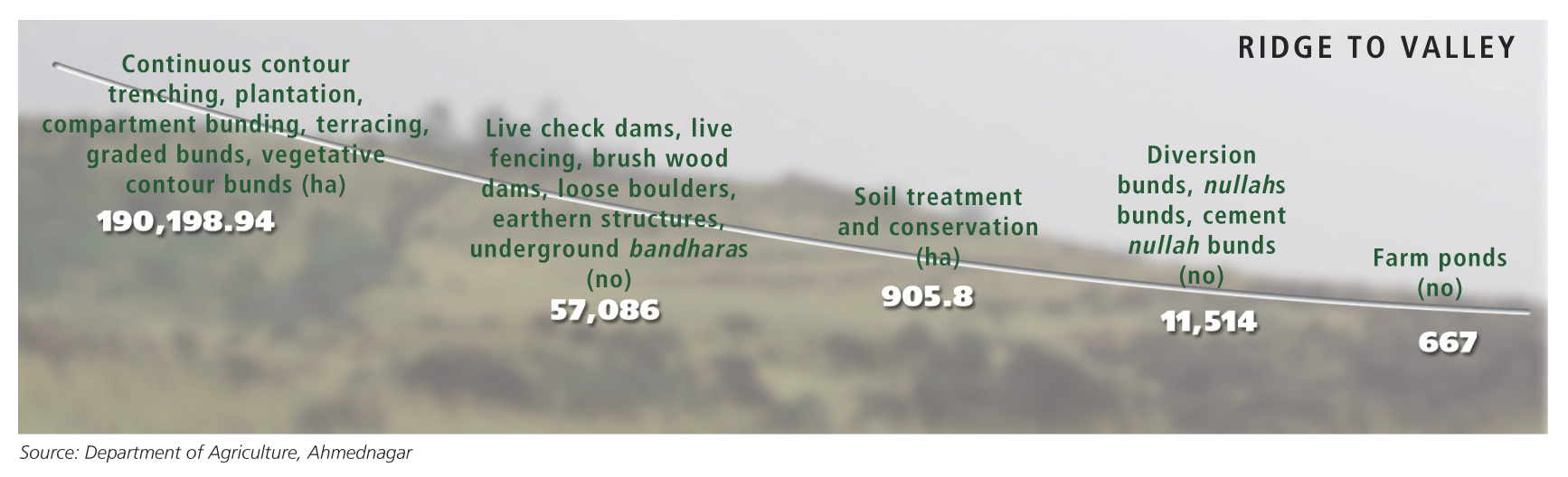

The Gram Sabha thus budgets water for the village and decides from the total water available the amount of water that can be used and for what purpose. Here, water for drinking purposes (of humans and animals) and for other daily uses gets top priority. After budgeting for drinking water, 70% is set aside for irrigation. The remaining 30 per cent is kept for future use by allowing it to percolate and recharge groundwater. Taking this broad framework for water use, a yearly audit is carried out to assess water availability and adjust use accordingly.

In the year 2004- 05, Hiware Bazar found a deficit of 86.5 million litres of water after receiving an annual rainfall of 237 mm. This was followed by another deficit year in 2005- 06 with 47.7 million litres after the village received only 271 mm of rainfall. “The village had changed its cropping pattern and priority was given to crops like moong, bajra and gram instead of wheat and rice. This sustained them through the shortfall and helped them handle the deficit experienced in 2004- 05. As a result the deficit of 2005- 06 did not have any major impact on the cropping pattern”, says Bagmar.

In 2006, (see Table 2) the village experienced 549 mm of rainfall and the village had a surplus of 1465 million litres of water available, which encouraged them to take up wheat on 100 hectares of land and jwari (a type of sorghum that needs moderate moisture to grow and is used as grain as well as fodder) on 210 hectares of land. However, in 2007- 08, the village again received less rainfall, about 315 mm registering a deficit of 456.3 million litres. The Gram Sabha again decided to reduce the jwari grown to only 2 hectares and wheat to 70 hectares in the village, again emphasizing on growing moong and bajra. People understand the importance of the rules in the village and hence there are few deviations.

The water audit has been very useful in ensuring sustainability of both agriculture and water available for drinking purposes for humans and livestock in the village,” says Popat Rao Pawar, the present Sarpanch of the village. During 2003- 04, when the rainfall was only 60% of the norm, drinking water scarcity pervaded the district with a few exceptions. Hiware Bazar was the only village in the city block that did not have to rely on water tankers.

[1] Water vapour arises fm the water stored in the harvesting structures and is hence taken as available.

Table 2: Water Sources and Quantities 2006-2007

.

Hiware Bazar is now reaping the economic harvests of water conservation. Increased grass production has resulted in increased milk production, from a mere 150 litres per day during the mid-1990s to 2,200 litres per day presently. In 2006 the income from agriculture was Rs 24 784 000. This means an average per capita agricultural income of Rs 1 652/month. This is almost double the Rs 890/month income level for India’s top earning 10 % of the rural population in 2004-05. With only 3 families below the poverty line according to a household survey conducted in 1992, there has been an unbelievable reduction in poverty.

.

In many ways, Hiware Bazar symbolises the problem of water management in villages. It also emerges as an example of how to fix the problem. Many villages around Hiware have taken up similar measures and achieved success but none yet to the extent of Hiware. In India, where it rains for roughly 100 hours of the year, the management of water is critical to water sustainability. The current water crisis in India is not about scarcity. As the Hiware Bazar experience shows, it is about the management of water resources so that the infrastructure is capable of reaching out to poor people. It is about deepening democracy so that communities can be involved in the governance of the resource.

In the context of NREGA, Hiware Bazar shows a model of how to use this Act for village development because NREGA priorititises water conservation. Currently, all of the more than 610 districts in India are implementing the NREGA, a scaled-up version of the EGS that Ahmednagar implemented successfully to fight drought and rural economic distress. Most of the districts in the country exhibit ecological and economic problems of varying degrees that can be fixed in a similar fashion. However, after two years of NREGA implementation, the programme awaits the realisation of its development potential. Like EGS in Ahmednagar, the NREGA has also unlimited development potential. Thus, Hiware Bazar, and for that matter the Ahmednagar district, offers some crucial tips to enable NREGA to replicate Hiware Bazar across the country.

Under NREGA, however despite a ‘non negotiable’ (the act is clear on this) focus on water and soil conservation, most of the money is being spent on building roads and buildings [Government statistics for the year 2006-07 from nrega.nic.in]. It is just a few states, already known for implementation of massive water conservation programmes, that are giving priority to water conservation. Except for five states, the 22 remaining states have negligible allocation for water conservation. Only three states account for 96% of total water conservation works under the NREGA.

There has also been a failure in understanding the real nature of employment in the country. Ecological assets like land and forests are the key employment sources for rural people in India. Any attempt to create employment must focus on these sectors. But our policies for employment generation have restricted themselves to employment per se, and completely ignored the fact that the generated employment opportunities need to be sustainable and allow the employed to move above the poverty line. Exclusive focus on the purely quantitative approach to employment generation has resulted in low quality of employment. The result: we do generate employment, but they become unproductive very soon, leaving people either unemployed once again or grossly underemployed. A large part of the funds spent under these schemes is used in more capital-intensive activities such as building roads and government houses, rather than in labour-intensive activities. Productive assets are not the priority. A road remains what it was — a collection of holes in the ground — because it has not been built to last. It has been built to be washed away, each season, so that employment can be guaranteed.

The second lesson comes from ‘how’ the drought relief money has been spent on regenerating and increasing environmental productive assets. In Hiware Bazar, nature now produces more environmental services. This has implications for the future as well. What has been done for water availability might also be done for forests through investments in alternate energy sources to biomass such as solar and wind energy. Examples of large-scale movements such as the Green Belt movement in Kenya call for massive replication of successful models like Hiware. The green belt movement is a programme begun under the leadership of Wangari Maathai. It started out as a tree plantation movement against deforestation in 1977. Today, it has turned into a women’s empowerment movement that spreads across Africa and other parts of the world. In Hiware Bazar, the village plan was a well thought out, integrated ecological plan. It first treated the forest, the catchments for the village wells. Then it took up water conservation. Soil conservation followed this. Changes in crop patterns were also collectively determined according to the water budget available year to year. All along, the Panchayat made sure that EGS money was being spent according to this plan. Doing this the village made the EGS a long-term development programme. And EGS created more productive and sustainable employments. The zero demand for works under the new NREGS in the village is an indicator.

The third lesson is the role of coordination between the ‘where’ and ‘how’ factors. The Panchayat, made different independent government departments work in an integrated fashion by changing the most dubious character of bureaucracies in the country: their stand-alone mode of functioning. The Panchayat engineered reform in local governance by evolving a plan (in conjunction with the Gram Sabha) that government departments implemented and were accountable to the Panchayat for. This made the EGS a community-owned programme despite being a state-wide government scheme. Government however has not empowered the Panchayats sufficiently to enable village level planning in the (approximate) 60% of NREGA projects that they are responsible for implementing. This may make whatever productive assets are created redundant. One need only look back to the first few drought relief works in Hiware Bazar before the Panchayat took over leadership to appreciate the risk. This will be the biggest challenge for NREGA. Conceptually, decentralization is part of the scheme. The village has to make a development plan; the district has to make a perspective plan; the projects have to be cleared by the Gram Sabha and implemented by the panchayat. The question now is how this scheme can replicate the lessons of Hiware Bazar.

The Hiware Bazar example is meant to be exemplary for development planners and practitioners and for students of planning and policy research, but a precise compilation of such cases will help even local communities in assessing their case and taking away the vital lessons from model cases. The case of Hiware Bazar is representative of the conditions in the country and what can be done to change them, however the importance of de-centralisation of power structures also emerges as a key issue. On paper the Panchayats are empowered to take matters into their own hands. This augurs well for flexibility in the rural development schemes, and can go a long way to ensure proper and multi-dimensional development, but lack of funds and uncooperative government departments hamper the true exercise of power at the local level by these institutions.

.

As wealth increases in Hiware, the visitor to Hiware can observe changes in the lifestyles of the inhabitants. Hiware has adopted a policy of one child per family. Not only are births down, but the preference for male children has been almost entirely eliminated. Apart from rising literacy and health, there are also changes in consumption patterns. While almost all Hiware’s farmers carry their milk to the dairy by bicycle, a few now come by motorcycle. The first cars have entered the village, soon to be followed by more. This slow but steady transformation of the metabolism of this small village is representative of a change that will soon encompass large parts of rural India. How will India’s ecological base handle this socio-ecological transition? What kind of development and growth can we envision for a country with a population of over a billion and dwindling resources?

Firstly, India’s economic growth will be fuelled primarily by local environmental resources. India will not have the luxury that Western economies had to import food from colonies for its billion plus population. Because India’s population relies so immediately on their environment, CSE argues for a new conception of growth, one that emphasizes the concept of Gross Nature Product or the “GDP of the poor” in addition to standard economic indicators. When a dam is built or when forest clearance leads to loss of access to resources for poor people, they are forced to buy these inputs they depend on from the market. GDP goes up, but the well-being of the population suffers. By the same token, one can make environmental investments, such as Hiware has done, largely based on voluntary labour, and the economic returns are substantial. One could calculate the labour invested in terms of hours worked in contour trenching, bunding and other watershed work, as well as the return to such work in terms of increased production due to the increased water tables. Such a calculation could be used as a powerful argument for replicating investments across rural India. This concept of investing in natural assets has important consequences for the future prosperity of the rural poor. Investment in creating renewable sources of energy and water will also be key.

Most energy in rural India comes from locally sourced biomass (fuelwood, crop residues, and animal dung). In many places, where the institutions are not in place to regulate sustainable extraction, this can lead to deforestation and consequent soil erosion. While LPG and kerosene fuels are highly subsidized by the government and used primarily by the middle and upper classes, an even better alternative is evident in some households in Hiware — the use of biogas plants for lighting and cooking. The government should subsidy the construction of biogas plants in rural areas – leading rural India up the energy ladder, but using renewable energy rather than developing a dependency on non-renewable energy sources. Biogas plants have the added bonus that the manure waste can still be used as fertilizer.

Another lesson from Hiware relates to India’s future availability of water. In particular, Hiware’s system of water auditing has important lessons regarding the concept of virtual water. Virtual water is a concept, first elaborated by Tony Allan from London, about the water needed to produce a commodity throughout its whole life cycle, be it a grain crop or a hamburger. Because agriculture is by far the activity that uses most water, the virtual water concept has been used to suggest that countries with water scarcity should adopt a policy of eliminating exports of water intensive crops, such as rice, or alternatively, should stop producing them and import them from other countries. However, there is a problem with this simplistic understanding of the concept. Firstly, because it does not differentiate between rain-fed crops and irrigated crops, nor crops irrigated with harvested “renewable” surface water, or those irrigated with tube wells fed from ground water. The virtual water argument can also have consequences politically, and regarding equity. If water is released from agriculture, and farmers grow lower-value crops with less water requirement, the released water could easily be sucked up by India’s thirsty cities rather than distributed more equitably among the rural poor. Finally, the virtual water concept gives no indication whether water is being used within sustainable extraction limits, which change from year to year depending on rainfall. While Hiware’s virtual water exports have multiplied within the last 20 years, it was always in the light of increased supply. The water audit process that they have instituted is a much better indicator of sustainable extraction and perhaps a better policy tool than the concept of virtual water, despite the fact that the water footprint as a concept has captured the imagination of CSOs and governments around the world. However, Hiware shows how the true distinction should be between living off the income of environmental investments rather than depleting limited environmental capital.