7. Final Remarks on Transdisciplinarity

Ecological economics, based on methodological pluralism (Norgaard 1989) must not follow the reductionist road. Instead it should adopt Otto Neurath’s image of the ‘orchestration of the sciences,’ acknowledging and trying to reconcile the contradictions arising between the different disciplines which deal with issues of ecological sustainability. Thus, how could a history of the industrialized agricultural economy be written taking into account both the viewpoints of conventional agricultural economics (technical progress, growth of productivity), and of agroecology (loss of biodiversity, decreased energy efficiency)? The image of the ‘orchestration of the sciences’ fits well with the ideas of coevolution and of emergent complexity; implying the study of the human dimensions of ecological change and therefore the study of human environmental perception. This means to introduce self-conscious human agency and reflective human interpretation in ecology. While ‘emergent complexity’ looks more to the unexpected future, ‘coevolution’ looks toward history.

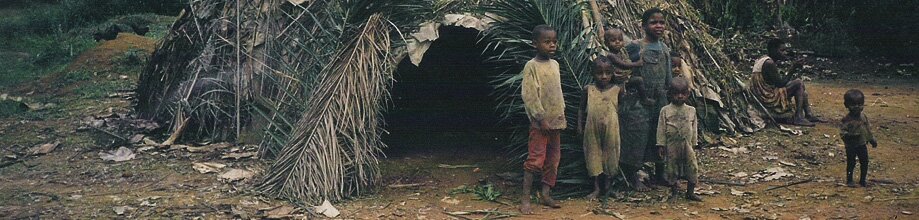

Ecological economics as an ‘orchestration of the sciences’ takes into account the contradictions between the disciplines, it also takes into account the changing perceptions through history of the relations between humans and the environment, and it highlights the limits of the authoritative judgments of any particular expert in a particular discipline. This is not a technocratic or scientistic project. On the contrary, as explained by Funtowicz, Ravetz and other students of environmental risks, in many current problems of importance and urgency, where values are in dispute and uncertainties (not reducible to probabilistic risk) are high, we observe that ‘certified’ experts are often challenged by citizens from environmental groups. Examples of these are popular epidemiology activists inside the Environmental Justice movement in the United States, or debates on nuclear energy or on the labeling of new biotechnological foods, or arguments based on the practical knowledge of indigenous and peasant populations. This is postnormal science, leading toward participatory methods of conflict resolution and even toward discursive democracy, notions which are dear to ecological economists.

1. Origins

2. Scope

3. Disputes on Value Standards

4. Environmental Indexes of (Un)sustainability

5. The ‘Dematerialization’ of Consumption?

6. Carrying Capacity and Neo-Malthusianism

7. Final Remarks on Transdisciplinarity

References